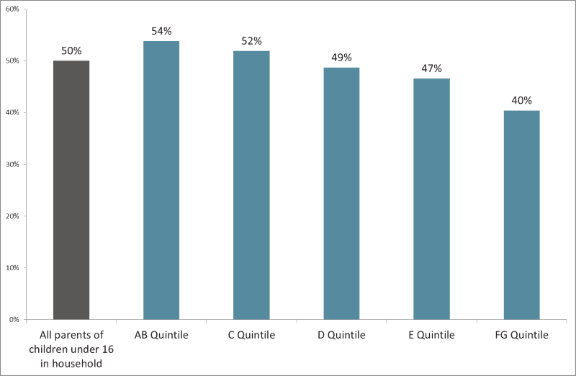

Overall, half of Australian parents with children under 16 living at home say they try to buy additive-free food, up from 45% in 2010.

But parents in the lowest socio-economic quintile are much less likely than those in the highest to agree.

In the top AB socioeconomic quintile, 54% of parents agree that “I try to buy additive-free food”, as do the majority of those in the C quintile (52%).

But less than half of all other parents say they try to avoid buying food with additives: from 49% of D quintile, 47% of E, to just 40% of parents in the lowest FG quintile.

Children mirror their parents

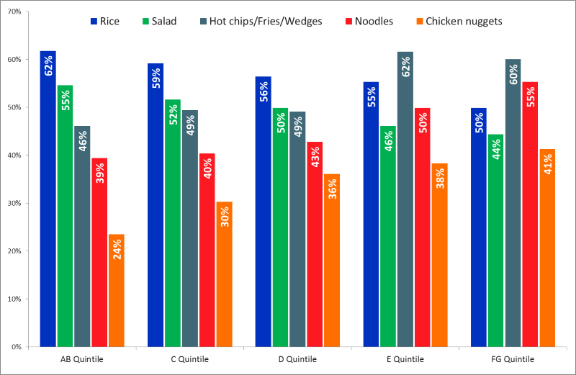

Children were also surveyed, and again the results show some big differences in the eating habits of children depending on their household’s wealth.

Over 60% of children aged 6-13 living in AB households would eat rice each week, while 55% eat salad compared to less than half eating hot chips, fries or wedges (46%) or noodles (39%). Only around a quarter eat chicken nuggets (24%).

But children’s eating habits change as household wealth declines. With each successive drop in socio-economic status, children in the household are less likely to eat rice or salad, and more likely to eat noodles or chicken nuggets.

During an average week, less than half of kids in E or FG homes eat salad, and more eat hot chips, fries or wedges than rice.

Mystery of the rice and noodles

“Our research into health attitudes shows that over the last five years an increasing proportion of parents are mindful of their own calorie, fat, dairy, and red meat intake; but are slightly less likely to be trying to limit how much sugar their kids eat,” said Michele Levine, chief executive of Roy Morgan Research

“While the food that parents buy and give to their children is heavily influenced by the affordability of groceries, there may be many other issues at play such as the number of children and parents in the household, working hours, accessibility of fresh produce in the local area, as well as underlying attitudes and tastes.

“For example, price alone does not fully explain the inverse changes in popularity for rice and noodles among children across socio-economic quintiles.”