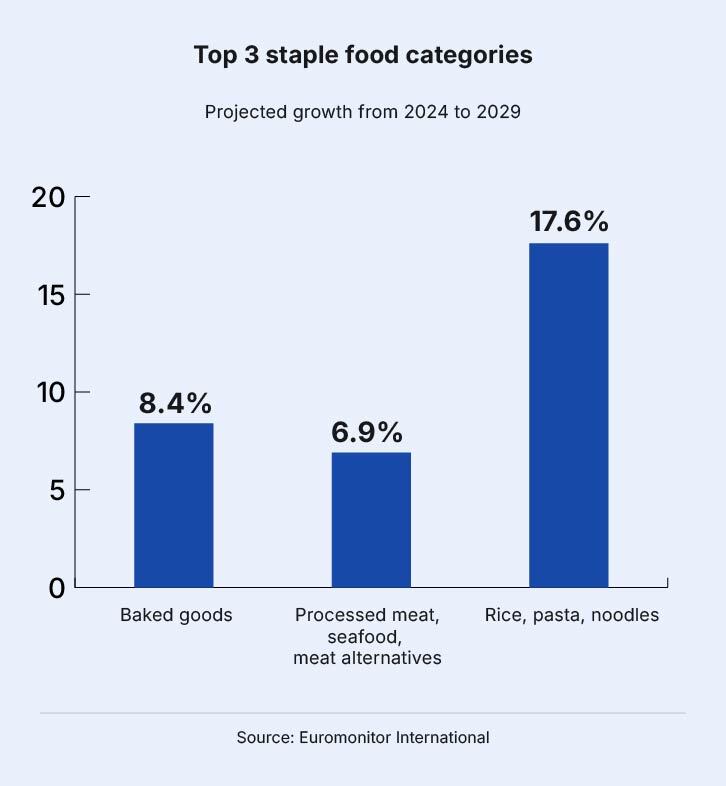

Staple foods such as rice, edible oil, sugar and salt are amongst the most traditional food categories in the food industry, with innovation having been limited over the years until recently when health and wellness became a major priority for consumers.

Even so, innovation in this sector has not been the most advanced or rapid, especially wen compared to other sectors such as snacks and beverages.

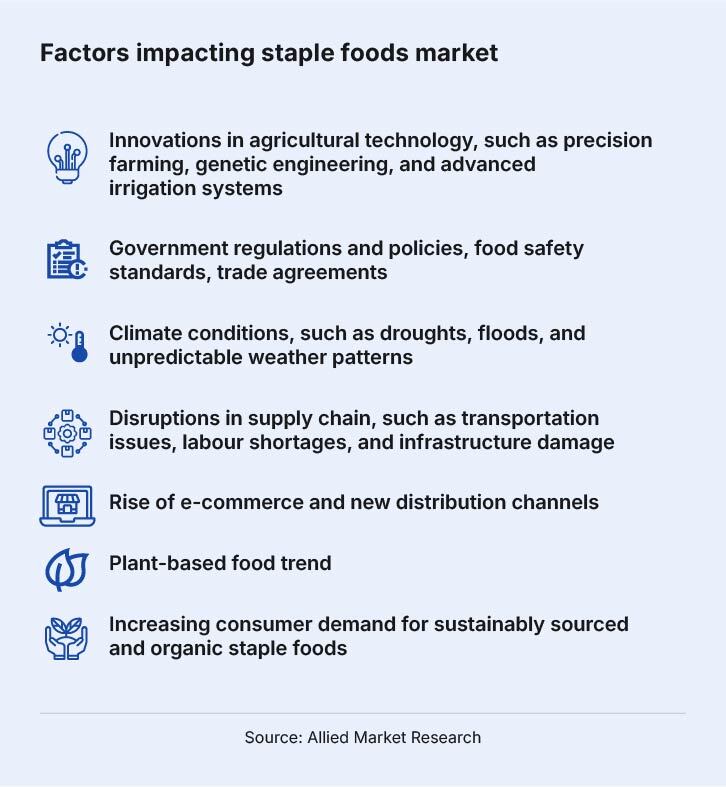

For grains such as rice and wheat, this has largely been focused much higher up the supply chain and far out of the consumer eye, such as the development of more climate-resistant rice variants, or pest-resistant wheat variants, efforts which can take years to culminate in tangible results for the food system.

That said, there have been areas in this space which have made breakthroughs - or comebacks, in the case of millets in India – and innovation has been taking place at a much higher rate than others.

“Rice and wheat are important crops, but are also very commercialised crops and we now know they are not the most sustainable in terms of water utilisation in farming,” India’s Yellowfield Organics Managing Director Garvit Raj Patodia told FoodNavigator-Asia.

“Rice had been our main grains business for a very long time, but we believe that there are other crops available which have enormous potential to substitute wheat and rice as staple foods both in India and other markets, such as millets.

“Millets can play an important role in food supply chain as this substitute, as they can be used to make noodles, pasta, bakery products and more, so product innovation is just at the beginning in this area and growing very fast as opposed to rice where innovation is quite rare.

“In addition to application, millets also have a much higher protein and fibre content as well as lower glycaemic index, so can also make enormous contributions in the food system from a nutritional perspective.”

Patodia added that even in terms of staple foods, consumers now know that regular staples like white rice and white bread may taste good but are not always the best for health, and are demanding more even from these basic items.

“In staple foods, more and more people are looking at a health focus and not just taste anymore,” he said.

“Previously it was common to eat to satisfy one’s taste buds, but now with this growing awareness, people are tending to eat for the good of the body instead.

“It is this that makes us believe that in the coming 25 years, millets are going to gain stronger status as a staple food beyond just India, but also to more parts of Asia and the world, with the potential to get on the level of current commercial crops.”

Watch the video below to find out more:

Rice and flour

That said, there can be no doubt that at the moment rice remains the number one staple food in the Asian and Middle East regions, though health and wellness have been clearly guiding trends in these markets as well.

“Many consumers and millennials in particular have become more health-conscious in the last decade or so,” rice industry heavyweight Gautam General Trading (GGT) Managing Director Gautam Aggarwal told us.

“There are consumers avoiding carbohydrate-heavy rice and increased demand for brown rice, but there is still huge consumption of white rice and especially basmati rice [due to its lower glycaemic index].

“Rice is [still a major] staple food, and low in fat, high in fibre, and gluten-free [so] while over-consumption of carbs is being avoided, [many consumers are aware of the need to eat] in moderation — a healthy and balanced diet should consist of both proteins and carbs, and rice is an excellent source [of the latter].

“We have however noticed a trend towards smaller pack sizes in the Middle East, likely because of a rising number of smaller families.”

In East Asian markets like Japan and South Korea, recent government initiatives have shown a rising interest in using rice flour to replace wheat flour for making various staple foods like bread and noodles.

A major motivator behind these initiatives was the Russia-Ukraine war, as these countries were major wheat suppliers previously making up about a quarter of the global wheat market, prompting concerns in importing countries like South Korea.

“Rice flour is very advantageous as a substitute for wheat flour [as] it has a dense starch structure and is not easily broken whilst processing – we will thus be activating rice flour to replace 10% of the demand for imported wheat flour by 2027,” South Korea Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs MAFRA Minister Jeong Hwang-geun said.

“[The hope is that] this replacement of 10% of the demand for wheat with rice flour will help to reduce reliance on imports and prevent price instabilities, whilst also providing Korea with a more stable food supply to increase local food self-sufficiency.”

Japan, which also suffers the unfortunate status of being the least food self-sufficient developed country in the world at just 38% according to its own data, hopes that shifting to rice as a substitute for wheat will help it increase its food self-sufficiency levels, given that rice is a crop that it can grow locally and better control production of.

“Rice is the only grain that Japan can hope to become self-sufficient in in the long run, hence we are intensively supporting efforts at every part of the supply chain from production, distribution and consumption to expand the usage of rice flour,” Japan’s Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries (MAFF) said via a formal statement.

“The approximate budget for projects in this area will be JPY3bn (US$20mn), and from a business and commercial perspective one of the goals is to increase rice flour production to 130,000 tons by 2030.

“Support will also be focused on the development of end-products in the food industry that take advantage of the characteristics of locally produced rice flour.”

Key priorities include food categories such as confectionery, bakery and another local staple, noodles.

It still has quite a long way to go to reach self-sufficiency though – 2023 government data indicated that rice self-sufficiency levels in Japan were at just 15%.

Sugar and salt

Within the salt and sugar sectors, innovation has been heavily influenced by health and wellness factors, including a need for wide scale reformulation driven by regulations.

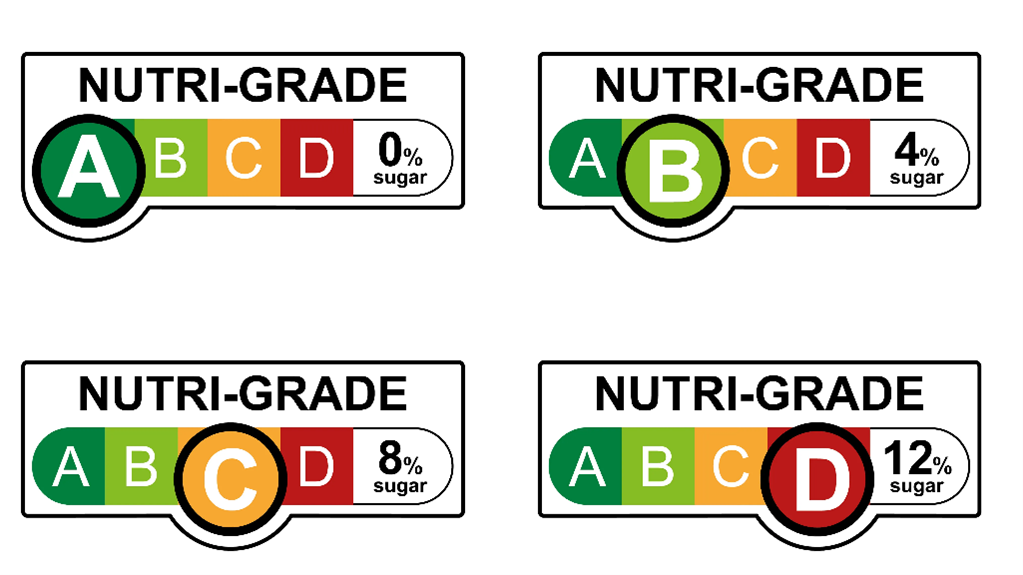

One of these has been India’s proposed Indian Nutrition Rating (INR), which has similarities with Singapore’s Nutri-Grade front-of-pack labelling scheme that was first introduced for sugar-sweetened beverages in December 2020, and is often credited with motivating many beverage manufacturing companies to reformulate their products with less sugar.

Many of these firms have created sugar-free or reduced-sugar versions of their products, the most well-known of these likely being Coca-Cola’s Coke Zero; or creating smaller formats/packaging sizes of these drinks.

“Coca-Cola is committed to making more reduced- and no-sugar versions of many of the drinks consumers love available and easier to find,” Coca-Cola India President Sanket Ray said.

“In 2023, 30% of the global Coca-Cola volume sold was low- or no-calorie beverages and about 68% of products had less than 100 calories per serving.

“For Coca-Cola India in particular, all leading sparkling brands have been implementing a zero- and low-sugar variant [which has been in progress] in a phased manner since 2022 - We know that consumers need choice, and because of this every brand will have a ‘zero leg’.”

Many sugar firms in APAC have also been innovating lower-calorie sugars or zero-calorie sweeteners in response to such regulations, as have various smaller beverage companies looking to enter new markets in the region.

“Under Singapore’s Nutri-Grade scheme, our original instant boba milk teas were rated as a D, so we reformulated our drinks and cut the sugar content from 14% to 5%, and reduced the fat from 2.8g to less than 1.2g fat per 100 ml [in order to move to] grade B,” Vietnamese instant boba milk tea brand Luave’s parent company Idocean’s Brand Manager Thao Le told us.

“Due to this Nutri-Grade regulation, Singapore will only carry the low fat and low sugar options while other Asian regions will have both original and healthier versions.”

Singapore announced late last year that the Nutri-Grade system would be extended to cover salt and fat in addition to sugar moving forward, prompting further concern from the food industry.

“It is important to consider that salt, sauces, seasonings and oil tend to only be present in small amounts in a dish [or product] alongside the main ingredients, with the amounts added varying depending on the discretion of the consumer or chef,” industry representative body Food Industry Asia (FIA) CEO Matt Kovac told us.

“These differences in consumption practices to beverages may render the extension of the current Nutri-Grade scheme ineffective in terms of assisting consumers to choose healthier options in this instance.

“Salt does not simply enhance flavour, it has multiple uses, such as retaining moisture and as a preservative [so] reformulating products to contain lower levels will not only impact taste but could impact food safety and shelf-life, adding further complexity to reformulation.”

Further concerns circle around cost implications due to the complexity of this reformulation, which would potentially result in price hikes that impact consumers further.

“The costs of sodium reduction vary significantly by category. Industry estimates that for up to a 25% sodium reduction, categories like ketchup and sauces could achieve cost parity while a 25% to 50% reduction could lead to a 10% increase in costs,” he said.

“In snack products with seasonings, a 25% to 50% sodium reduction could incur a 10% to 20% incremental cost, as may bouillon cube seasoning blocks.

“A proportion of these costs may need to be passed on to the consumer, which may impact the likelihood of consumers switching to lower sodium alternatives.”

Potential solutions have been suggested by players such as Ajinomoto which has long promoted amino acids’ umami flavour as a potential sodium replacement option, as well as Kirin which created an electric spoon with a ‘unique current waveform’ to enhance the perceived saltiness of food when in use.

One of the markets currently most in need of such solutions is Indonesia, due to both consumer health and regulatory reasons.

“Salty foods and many convenience foods are high risk factors everywhere, and in Indonesia this risk is even higher as this includes many of our common daily foods,” Bogor Agricultural University Nutritional Science professor and Ajinomoto Indonesia spokesman Professor Dr. Hardinsyah said.

“There are many examples of this, e.g. salted fish is consumed in large amounts in mountainous communities, and we have over 100 varieties of bakso meatball soups across the whole of West Indonesia, almost all of which use a lot of salt,”

“Research in South Jakarta has shown that Indonesians consume between 5.76g to 7.43g of salt daily, with the highest sodium content found in chilli sauce which is another staple Indonesian favourite.”

Indonesia also recently proposed a Nutri Level FOPL scheme that is expected to look and function similarly to Singapore’s Nutri-Grade.

Edible oil

As these regulations would also take the fat content of foods into account, there would also be impacts on the vegetable oils, which is considered another staple food category.

Palm oil is the most common and widely used vegetable oil for cooking and food manufacturing in both Asia and the Middle East, and for this sector the biggest topics of discussion, which have also been driving innovation, have undoubtedly been sustainability and health.

“[When looking at edible oil, and particularly the specialty fats category], there is certainly a trend to note around snacking and smaller portions,” Golden Agri-Resources (GAR) Managing Director for Africa, Middle East and South Asia Imran Nasrullah told us.

“You’ve got people taking weight loss so seriously that they’re even taking medicine, and this is a trend which is changing the consumption of foods, such as less fried foods and smaller pack sizes.

“For the Middle East, incomes in this part of the world are rising and populations are growing, and as that happens, more people are demanding more different kinds of foods.

“So for us in [this] business, specialty fats is probably is going to grow very fast as people are going to demand specialised kind of foods – e.g. following the weight loss trend, people may reduce the amount people eat, which means that they want higher nutrition quicker but in smaller sizes, so we have to adapt accordingly with strategies such as different portion sizes or packaging sizes.”

In terms of sustainability, the debate has been raging most strongly around the EU deforestation regulation (EUDR) which will be enforced at the end of the year, and the palm oil sector has largely been leading the charge.

With the implementation of EUDR imminent, much of the conversation has turned to the need for added sustainability-focused funding for not just palm oil but all agrifood sectors in order to accelerate sustainable change.

“The agrifood space is receiving just 5% of all transition funding globally, so we can say that sustainability efforts in this sector are severely underfunded,” GAR Chief Sustainability & Communications Officer Anita Neville added.

“It is not just palm oil that is being affected - this concerns all major staple foods, from rice to coffee to edible oils.”

Challenges

Sustainability concerns unfortunately also plague many other staple food sectors – Yellowfield was a major player in the rice industry for many years before taking on millets into its portfolio, and is well-placed to highlight some of these issues.

“Rice actually uses a huge amount of water to grow. It is also the most-consumed grain, resulting in a huge reliance on it, and as a result there are markets that face huge shortages especially during times of drought,” Patovia said.

“This is why we believe millets are a good substitute as these use less water, and can grow all year round, without the need for rainfall. The time from planting to harvesting time is also much shorter, around 60 to 90 days.

“The main challenges millets face currently is mostly because it is relatively new, so consumers, particularly outside of India, tend to not be sure how to use and apply in the kitchen when it can actually be boiled like rice or made into flour or pasta, and much more.”

Aggarwal added that climate change has been a major challenge even for traditional rice companies, but technology has been a saving grace.

“Rice is a volatile commodity like sugar and gold [and] basmati rice is a very sensitive crop, so factors such as increase or decrease in temperatures and rainfall impact yield significantly,” he said.

“But while climate change has made it more challenging to manage rice crops, technological advancements in agriculture have helped improve both the quantity and quality of yield.”